The Devotion at Gettysburg

Nineteenth century America was a nation of immigrants. This first installment of my five-part serial blog essay begins with the story of one of those ethnic groups - the Irish Americans. Orr is an Irish surname. My ancestor James Orr emigrated to the colonies in about 1758. At least three of my great-grand uncles and multiple cousins with that surname served under the star-spangled flag with West Virginia regiments. Thus my interest in the Northern Irish of the Civil War. But the famous Irish Brigade was recruited from the boroughs of New York city. At the start of the war, the brigade was comprised of three New York regiments (63rd, 69th, 88th) of which 2,500 men enlisted. Afterwards, the non-Irish 29th Massachusetts joined (to be replaced later by the Irish 28th Massachusetts) the brigade along with the Irish 116th Pennsylvania regiment (more to come on them in a later blog).

There are by current count 1,328 monuments/memorials/tablets/markers at Gettysburg National Military Park (GNMP). Of these, the Irish Brigade monument is arguably the most beautiful one at the GNMP. It was erected on the Stony Hill in 1888 to commemorate only the three NY regiments1. The monument consists of a polished granite shaft which top has been carved into a Celtic Cross, the iconic symbol of Ireland. It has a bronze inset of five medallions: the three regimental numbers, New York state seal, and the seal of Ireland. At the base of the shaft lies a life-size bronze sculpture of a Irish Wolf Hound. It is one of only two Gettysburg monuments depicting a dog. The Wolf Hound represents faith, devotion, and loyalty. In Lincoln's Gettysburg address, he refers to the battlefield dead as giving their "last full measure of devotion". Is there any living creature that is more devoted to its master than a dog?

The founder of the brigade, Thomas Meagher, was a steadfast Irish Nationalist. Consequently, most of the brigade's leadership were known fellow Irish revolutionaries. Meagher believed it was important for the Irish-born to fight for the Union. Even with its influence dwindling since 1855, the anti-immigrant policies of the Know-Nothing party were still a powerful political force, with some former party members having infiltrated Lincoln's Republican Party. Meagher promoted military service as a way for Irishmen to overcome the Nativist indoctrination and to demonstrate their loyalty to the nation. In addition, Meagher was convinced that British sympathy lay with the Secessionists, which much evidence suggests to be true.

Why did the Northern Irish fight? This is a complex question with a complex answer. Foremost, one cannot understand the answer unless one has an understanding of mid-nineteenth western European history2. My own opinion is that a display of loyalty on the part of the northern Irish was driven by both the need to gain ethnic acceptance from the majority status quo and their disenchantment with previous European strife in the early and mid-nineteenth century. These immigrants not only wanted to belong to this young nation, but they wanted to settle this division between the North and South once and for all so that their descendants and future immigrants could live in both peace and harmony in a United States. However, there is another angle. In 1861, James McKay Rorty, of the 69th New York regiment, wrote to his father that he enlisted for the sake of his homeland, saying that he hoped “that the military knowledge or skill that I acquire might thereafter be turned to account in the sacred cause of my native land.” Rorty also said he fought for future immigrants, writing that a Southern victory would “close forever the wide portals through which the pilgrims of liberty from every European clime have sought and found it. Why, because at the North the prejudice springing from the hateful and dominant spirit of Puritanism, and at the South, the haughty exclusiveness of an Oligarchy would be equally repulsive and despotic…Our only guarantee is the Constitution, our only safety is the Union.”

In summary, the Irish did not want war, and favored the cause of neither side, North or South. Their cause was primarily driven by their love of their native motherland. As an oppressed minority, they may have had some empathy for the slave only due to their hatred of the South's slaveholding oligarchy, which reminded them of the privileged Protestant landowners that they had fled from in Ireland3. And they resented the Puritanical bigotry of the Northern status quo against their ethnic group. Thus they had no shared interest with either the abolitionists nor the secessionists. But as a refuge for fellow future Irish immigrants, a free, undivided America offered hope, and as both Rorty and Meagher documented, a future for the next fight against the British Empire. Consequently, some will question whether the Irish Brigade's devotion was to the Union, or toward the overthrow of British rule in Ireland (Some of these soldiers were in fact members of the Fenian Brotherhood, an organization committed to securing Ireland's freedom). Some Irish-American soldiers no doubt may have thus seen the Union Army as a necessary evil to another end, and viewed himself as more of an ally of the Army of the Potomac rather than as a member of it. But far more Irish-American volunteers likely wished to preserve the union as an end to itself. Playing on themes of gratitude and obligation, Irish-born recruitment methods stressed to the immigrant that it was the United States that gave the nation-less Irish “liberty, a shelter and a home."4

After the devastating Battle of Fredericksburg in December of 1862, General Meagher requested the government to recruit the brigade back to full strength, to which his request was denied. Five months later, when the brigade sustained further casualties at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Meagher repeated his request to recruit replacements and was denied. In protest he resigned his commission as leader over the Irish Brigade and was replaced by Colonel Patrick Kelly. Prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, the brigade was able to field about 530 men under the Division command of John Caldwell. This brigade number is a foretelling war casualty rate in that it represents about a normal half-strength regiment. Days prior to the battle, a soldier asked a fellow soldier the name of the regiment marching past. The soldier replied, “that’s not a regiment, that’s the Irish Brigade.”

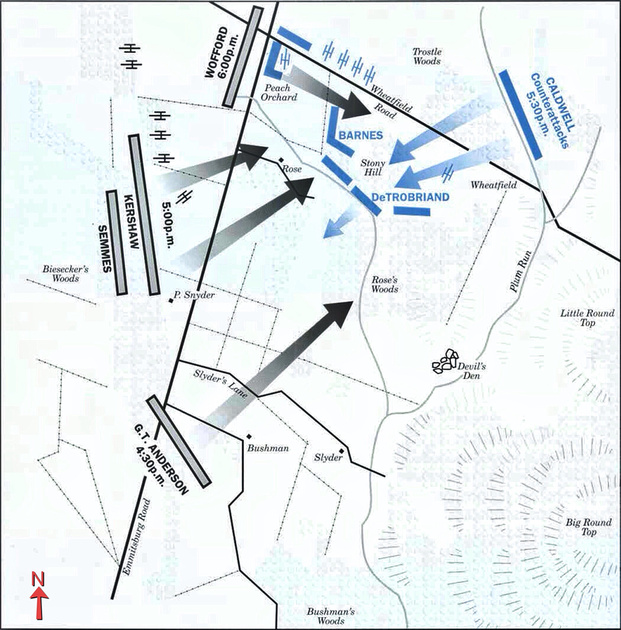

Late afternoon on July 2nd, 1863, day two of the Battle of Gettysburg, General Winfield Scott Hancock, the charismatic field general on day one of the battle, and who had resumed Second Corps leadership, ordered Caldwell's division to relieve Sickles' troops at the Wheatfield. Prior to the orders, Caldwell's troops had been waiting for ten hours at a reserve position behind Cemetery Ridge. The brigade head chaplain was Father Corby, who offered a prayer for the many soon to be troop casualties, prior to their deployment. He reminded the men that the "Catholic church refuses Christian burial to the soldier who turns his back upon the foe or deserts his flag." He then raised his right hand and pronounced the Latin words of general absolution. Per Corby's memoirs, even the cantankerous and profane Second Corps commander exhibited piety: "Even Major-General Hancock removed his hat, and, as far as compatible with this situation, bowed in reverential devotion." Colonel Mulholland of the 116th Pennsylvania wrote, "I do not think there was a man who did not offer up a heartfelt prayer. For some, it was their last; they knelt in their grave clothes." See more about Father Corby's absolution and monument at the GNMP here.

The Wheatfield battle ground covers the Rose family owned 20-acre wheatfield plus an adjacent wooded, rocky knoll, now known as the Stony Hill. The Wheatfield fighting was intense, chaotic, close range, and included hand-to-hand combat. The Irish Brigade fought mostly on the Stony Hill west of the Wheatfield. There were several attacks and counterattacks by thirteen brigades in a 3-hour period of which field control changed hands at least a half dozen times. At about 5:30 p.m., Caldwell's division arrived for the fight and three of his four brigades, under Colonels Kelly (the Irish Brigade), Zook, and Cross5 moved forward. Zook and Kelly drove the Confederates off of Stony Hill while Cross cleared the Wheatfield. Both Zook and Cross were mortally wounded in leading their brigades through these assaults. Described as a whirlpool by some veterans of the conflict, one Union soldier recalled "how the ears of wheat flew in the air all over the field as they were cut off by the enemy's bullets". At one point, the two sides blazed away at each other at less than 30 paces for about ten minutes. Then Colonel Kelly ordered his brigade to charge three South Carolina regiments and swept them off the hill. Later, surrounded by new advancing Rebel troops at the nearby Peach Orchard6, Kelly ordered his five regiments to fall back to Cemetery Ridge. Brooke's Brigade, held in reserve, was ordered by Caldwell to sweep the Rebels clear of the Wheatfield, which they accomplished, but Semmes' Georgia Brigade7 counterattacked and regained possession of the field. US Regular troops and the Pennsylvania Reserves (Bucktails) were called in to relieve Caldwell's Division. Prior to sunset, after more heavy Wheatfield fighting, the Pennsylvania Reserves drove out the Confederates and took control of the eastern stone wall of this hotly contested land of wheat. For the rest of the second day battle, the bloody Wheatfield would remain relatively quiet, but not so for Cemetery Ridge8. A heavy toll was paid by both sides for the back-and-forth trading of field possession. The Confederates had fought four brigades against nine smaller Federal brigades, and of the 20,000 men engaged, there were about 30% casualties. For the Irish Brigade, the Wheatfield Battle cost the brigade 214 casualties out of 530 men9.

The Irish Brigade will be remembered as having made some of the most gallant charges of the Civil War: The Bloody Lane at Antietam, Marye's Heights at Fredericksburg10, and the Wheatfield at Gettysburg. Per a well referenced book by the author William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, of all Union army brigades, only the 1st Vermont Brigade and the Iron Brigade suffered more combat dead than the Irish Brigade during America's Civil War. Eleven of the brigade's soldiers were awarded the prestigious Medal of Honor.

Note1: Father Corby was present at this dedication.

Note2: Refer to this excellent series, The Immigrants' Civil War

Note3: Although labor competition complicated that viewpoint, see the New York City Draft Riots of 1863

Note4: There were about 40,000 Irish soldiers fighting for the Confederacy, including the famous Major General Patrick Cleburne and his brigades. Significantly fewer Irish-Americans lived in the southern states. The Union’s Irish Brigade was unique in that it was composed of mostly Irish recruits. The Confederacy was not able to consolidate its southern Irish into large military units. The Irish were distributed throughout the South’s regionally raised regiments, where some company-sized units were formed from mainly Irish volunteers. Companies with mostly Irish recruits came from South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Missouri, Alabama, and Louisiana.

There are some who would claim that the Confederate Irish supported the South's cause since they could identify with the desire for self-determination and the right to secede from what was perceived as a repressive government. I am not convinced of this argument at this time. More valid research is required to support such stated claims.

Note5: More to come on the Warrior Edward E. Cross and his Fighting 5th New Hampshire Regiment in my next and second of five blog posts, The Honored Dead at Gettysburg.

Note6: Be sure to watch out for my upcoming third of five blog posts on The Struggle at Gettysburg (The 114 Pennsylvania and Barksdale's Charge through Mr. Sherfy's Peach Orchard).

Note7: Be sure to watch out for my upcoming fifth of five blog posts on The Consecration at Gettysburg (The 116th Pennsylvania and Semmes Brigade at Gettysburg).

Note8: Be sure to watch out for my upcoming fourth of five blog posts on The Bravery at Gettysburg (The Gallant Charge of the 1st Minnesota at Gettysburg).

Note9: For more detail on the Irish Brigade at Gettysburg, see the 12-part series at Gettysburg Daily.

Note10: See below the Don Trioani print, Clear the Way, depicting the famous Irish Brigade charge at Marye's Heights on December 13, 1862.

For some absorbing anecdotes concerning the Army of the Potomac, see Dr. Timothy Orr's blog: Tales from the Army of the Potomac.

My full Gettysburg gallery of photographs can be found at D.W. Orr Gettysburg Gallery.

D W Orr

Environmentalist, Historic Preservationist, Weimaraner Companion, Blogger, and Photographer

Harford County, Maryland

December 5, 2015

Irish Brigade Monument

Irish Brigade Monument - Wolf Hound

Irish Brigade Monument - 63rd, 69th, 88th New York Regiments

Irish Brigade Monument - Wolf Hound: "This - in the matter of size & structure, truthfully represents the Irish Wolf-hound, a dog which has been extinct for more than a hundred years." - William Rudolf O'Donovan (Sculptor)

Irish Brigade Monument - Wolf Hound: "This - in the matter of size & structure, truthfully represents the Irish Wolf-hound, a dog which has been extinct for more than a hundred years." - William Rudolf O'Donovan (Sculptor)

Irish Brigade Monument - Celtic Cross

Irish Brigade Monument - Back View

Irish Brigade Monument - The Wheatfield is in the left background

Father Corby Monument at Gettysburg

Father Corby Monument at Gettysburg

Father Corby Monument at Gettysburg

Father Corby Monument at Gettysburg

Irish Brigade charges the stone wall at Marye's Heights - Battle of Fredericksburg (Clear the Way by Don Trioani courtesy of Gettysburg Daily)

Caldwell's Division Advances into The Wheatfield (Map courtesy of NPS)

42nd Pennsylvania Infantry Monument on the Stony Hill (13th Pennsylvania Reserves or "The Bucktails") - Relieved Caldwell in The Wheatfield

42nd Pennsylvania Infantry Monument on the Stony Hill (13th Pennsylvania Reserves or "The Bucktails") - Relieved Caldwell in The Wheatfield